Disney and Pixar: The Lessons AI Folks Can Learn from CGI Replacing Hand Animation

Rapid Societal Shift, Adapting to Technology Constraints, Attracting Talent, and Paying the Price of Late Adoption

I want to tell you about two movies that represent the beginning and end of one of the most dramatic shifts an industry has ever seen, over the shockingly short span of nine years. More importantly, I want to share the lessons that story contains for those of us in the field of AI. Those lessons include:

Technology adoption happens at viral speeds

Early adopters thrive within the constraints of nascent technology

Late adopters lose the talent war

Late adopters can still win (if they’re willing to pay the price)

A Tale of Two Movies

The first movie is one you may not have heard of: Home on the Range, released in 2004. Home on the Range was made by the venerated Disney Animation Studios, who had made dozens of highly successful hand animated films over several decades. As recently as the early 90s, they had created classics such as Beauty and the Beast and The Lion King, but something started going wrong as they entered the 2000s. By the time Home on the Range released, things had come to a head. A critical and commercial failure, Home on the Range was a sign of the times, a signal that a pivot had happened somewhere in the animation industry and Disney Animation had missed it. That pivot began a mere nine years earlier.

That brings us to our second movie, one I can almost guarantee you’ve watched: Toy Story. Considered one of the greatest films of all time, its a classic that spawned a massive franchise. While the Toy Story IP is considered a bedrock of the Disney media world today, it didn’t start that way. Toy Story wasn’t even made by Disney. It was made by a little studio known as Pixar, a spinoff of Lucasfilm purchased by Steve Jobs in 1986. Pixar wanted to be in the business of creating animated films. There were a few problems though. First, Pixar had never released a full length animated movie before Toy Story. Second, they were going up against Disney, who had built an empire on decades of highly popular and successful animation films. But the third and biggest difference is that Pixar wanted to make a film using only computer generated imagery, or CGI.

No one had ever released a film that was 100% CGI. It was unheard of. Up to this point, the primary method of animating a film was through hand-animation, a laborious process that required hundreds of skilled animators and artists. Pixar’s tiny team was proposing that they could create a compelling, emotional, artistic film using CG, which at the time quite frankly looked awful.

Yet despite the odds and the limitations of the technology, Toy Story was a smash hit. So was A Bug’s Life. And Toy Story 2, and Monster’s Inc., and Finding Nemo, and The Incredibles. Between 1995 and 2004, Pixar released hit after hit, all made 100% with CGI.

Meanwhile, Disney Animation films, still done by hand, began to inexplicably see lower and lower numbers at the box office. Movies like Dinosaur and Treasure Planet received mixed reviews and struggled to reach the high box office numbers of previous films.

Home on the Range was the final nail in the coffin. Disney Animation once again released a hand animated movie, despite the writing on the wall that things were going south. Upon release, critics and audiences reacted negatively. Disney Animation declared that Home on the Range would be their final hand animated film, and that moving forward they would plan on all films being made with CGI. While there have been some exceptions to this, overall CGI has become the near-universal way that animated films are created over the last 20 years. Not only that, CGI is used in nearly every live action film as well, from The Avengers to Avatar to The Lord of the Rings.

Lesson 1: Technology Moves Fast

Nine years. That’s all it took for an industry to go from hand animation to CGI as the default choice. When the ChatGPT moment happened, many individuals made bold predictions that within a decade, practically everyone would become reliant on AI. Skeptics shook their head, believing such a seismic shift in a short period of time was impossible. But history has demonstrated that impactful technologies can rapidly proliferate in an almost pandemic-like manner. Today we’ve discussing animation, but similar tales can be found in the history of cars, airplanes, electricity, railroads, computers, the internet, and more. AI appears to be on that same track.

However, the story of Disney and Pixar has unique relevance for business leaders looking to evaluate the risks of losing the AI race. There are three questions from the Pixar story that have massive implications for AI adoption.

How did Pixar make CGI work despite its limitations?

Why did Disney Animation movies stop working?

How did Disney Animation end up winning by the end?

Let’s answer those three questions with three lessons for AI adopters.

Lesson 2: Early Adopters Work Within the Constraints of Technology

How did Pixar sell CGI movies despite the shortcomings of the technology?

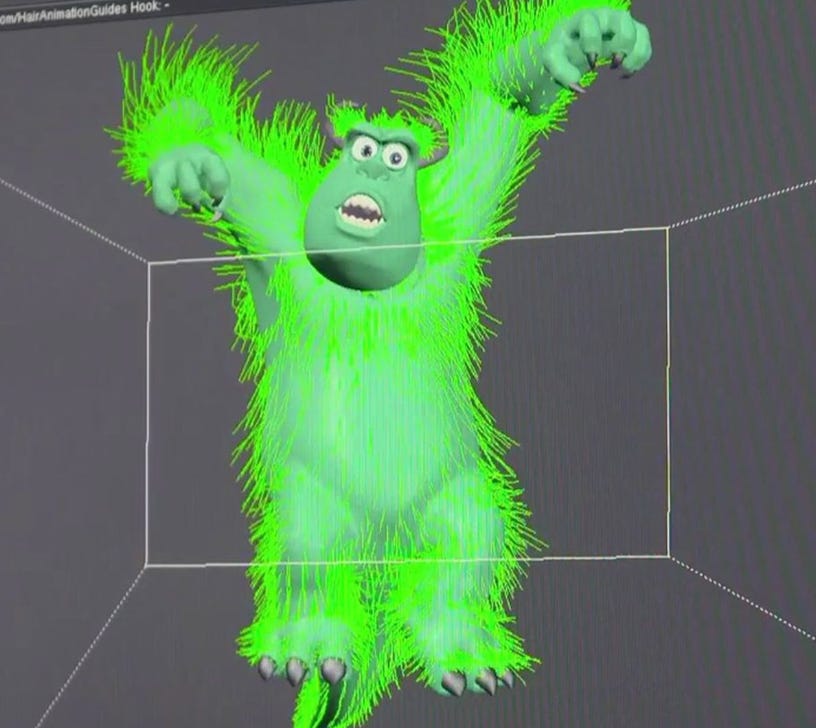

Early CGI was terrible, but Pixar was able to successfully work with those limitations. If CGI looked like plastic on screen, then the solution was to make a movie about plastic toys. Thus, Toy Story was their first movie by necessity. By working within the constraints of technology, Pixar was still able to express artistic creativity and build an emotionally impactful film. The success of the first film laid the foundation for them to slowly expand the ability of CGI. Monster’s Inc. added fur simulations, Finding Nemo added water simulations, and so on. By iteratively building upon the technology and slowly expanding its capabilities, Pixar was able to overcome those early limitations.

Lesson 3: Late Adopters Lose the Talent War

The success of Pixar is only half of the equation. Why did Disney Animation films stop winning?

There is nothing inherently wrong with hand animation. Clearly, decades of success proved that hand animation worked. Movies like The Lion King are still an enjoyable watch to this day. However, Home on the Range is not. What went wrong?

The first and obvious argument is that the efficiency gains from switching to CGI allowed Pixar to serve animated films at a lower cost, at a faster rate, with a greater ability to rapidly iterate and improve scenes through their technological advantage.

Such a sterile view of art through the lens of raw efficiency gains falls short of answering our question though.

I propose a second, more important reason Disney Animation films stopped working.

Disney Animation lost their talent edge due to falling behind the technology curve.

Imagine this. You’re a recent college graduate from the top art program in the nation. Your lifelong ambition is to make animation movies. Growing up, you had watched Disney and assumed a job at Disney Animation Studios was the logical endpoint for the journey you began by studying art and animation.

But as you drew close to graduation, a new kid on the block appears: Pixar. Their movies are a breath of fresh air. Modern humor. Heartwarming stories. But most interestingly, they seem to be forging the path of where animation is going. You have an opportunity to get in on the ground floor and create art with cutting edge technology. Or, you can go work at Disney Animation and painstakingly hand draw background characters twelve times per second of film.

The choice is obvious to us, and it was obvious to talent at the time. The best artists, screenwriters, and actors were all drawn to CGI as the new medium. They saw the writing on the wall. CGI was the future of filmmaking. Not only are modern animated films made with CGI, but so is practically every other movie as well. Whether you are watching horror, comedy, drama, or action, CGI is used to enhance hundreds of scenes across cinema.

By losing the talent war, Disney was left with second tier talent and bureaucracy that refused to take risks and thought making an animated film in the style of a Western was a safe bet.

The same applies to companies today. Employees are not stupid. They see the writing on the wall as well. They want to work at companies that are quick to adopt AI and position themselves as leaders of the new technology wave.

How can large enterprises ensure their employees are positioned to succeed with AI?

The same way Disney did. After announcing they were ditching hand animation, they gave free training courses to all of their hand animators so they could learn CGI if they wanted. Many employees took the courses, re-skilled, and went on to have successful careers. Some employees chose not to, and those animators had to fight over the few remaining opportunities for hand animation.

Lesson 4: Money Can Save Late Adopters

The story doesn’t end in 2004 though. The Mouse always wins.

The truth is, I’ve left out some key details in my storytelling. During this nine year period from 1995 to 2004, Disney funded all of Pixar’s movies, and handled distribution for them as well. A complicated legal relationship between the two meant that Pixar was financially bound to Disney.

And in 2006, Disney bought Pixar outright, finally bringing the circle to a close.

Disney immediately moved the best talent into Disney Animation, where they began working on new animated films built with CGI. Within a few years, Disney Animation was back on top, with films like Tangled and Frozen dominating the box office. Meanwhile, Pixar powered through with a few more hits before slowly experiencing the same talent drain problem Disney had faced earlier. Today, Pixar struggles to make successful movies that are not sequels, with several notable box office duds in recent years. Sony Picture Animations is now the ‘new’ kid on the block, taking risks with new technologies and art styles in movies like Into the Spiderverse and KPop Demon Hunters.

Companies are discovering the same lesson today with AI. Money can atone for the sins of late adoption. Mark Zuckerberg found this out the hard way when Meta began falling behind (see our story on their trillion dollar mistake). Acqui-hires are happening left and right, with big companies snapping up smaller startups to stay competitive. If you’re a big company falling behind, consider injecting your company with new life via an acquisition. If you’re a small startup jostling for attention, consider carefully if you want to go to war with the big players or aim for acquisition.

The bottom line: The race to adopt AI is more intense than ever. Companies recognize the risks of falling behind include not just losing the technology edge, but also the people edge. As organizations evaluate how to move forward, acquisition and talent attraction remain key cornerstones for staying ahead of the competition.